I pick the last row in the back of the bus and manage to stick myself in the corner. The blue seats are splashed with streaks of yellow. My seat seems to have more streaks than the rest. As soon as I’m settled in it, I put my earphones in and the slow beat of Majida Al-Roumi’s Kalimat [words] starts to prepare me for the night I am dreading. My black dress, faint nude lipstick, and the Arabic coffee I hold in my hand – blonde and bitter in a carefully chosen clear mug – make me feel as though I can handle going dancing with my classmates. I look beyond the windowsill at the pale blue sky. I hear my mother’s voice, disapproving, in my head. “You need more pink in your look,” she says, her voice adamant like the crease between her eyebrows. So I pick up a paintbrush and add shades of rose to the boyish blue that the sky prefers.

Just as I am starting to like my own company – which happens less and less often these days – a young man in a suit takes the seat beside me. He asks me what I’m listening to. I tell him it’s the voice of a woman telling a story about a man who whispers charming words into her ear as they dance. He takes her from beneath her arms and plants her in a cloud, carrying her as though she were light as a feather. He gives her the sun and the summer whilst telling her that she is his masterpiece, a treasure, and the most beautiful painting he has laid his eyes on. His words make her forget the dance floor and all the steps. His words overthrow her history and make a woman of her. He builds her a castle made of fantasies, but she goes back to her table alone, with nothing but words.

The man in the suit remarks that I must love this song. With a faint smile, I tell him that I hate it. He asks me why. The song is about words, I think to myself, but I say nothing. Picking up the conversation again, he asks me where I’m from. He smiles smugly, as though patting himself on the back for assuming I am a foreigner. I tell him, “I’m Saudi.” Although his feet remain firmly on the ground, he takes me from beneath my arms, just like Majida. Instead of planting me in a cloud, he swirls and twirls me, raising me up high, my identity seeming light as a feather; he locks me in a stereotype. I stay with the pink sky. He tells me how I probably feel free here in Canada. He comments on how strange it must feel to be able to leave the house without a man by my side, how lucky I am to be in a country where I am allowed to think for myself. He rains words, such words, on me. I melt the pink into a more muddled lavender shade; I am painting the damn sky and he insists on painting my life. How utterly boring.

I stand up and try to pass, but he refuses to move his legs. He ignores me and continues his dance. He spins me and whirls the words on his tongue, this time in another direction. He tells me that I am the most beautiful painting he has laid his eyes on, worth boundless stars. He builds me a castle out of his own fantasies, but his castle is merely the bus that I am trying to escape. He tells me that the men in my country are savages for locking up such enticing women. He overthrows my history with his words. His words don’t make me a woman. They make me a treasure. A symbol of worth. A thing.

I tell him I am not interested in this conversation, and I ask him to please move his legs. He says sway with me, I say no. He says it wasn’t a question, I say it should have been. He says I didn’t know Arab women were feisty, I tell him to fuck off. He says no, and I say it wasn’t a question. Move your legs now. He says he’ll allow me to pass if I answer one question: would I go back to Saudi? I tell him I’m not playing his game. I don’t want him to know that the answer is no. Now move. He smiles and remains stiff as his bigotry. Another man standing by the door interferes and tells him to move. Before a man could be more respected than my own demands I hop onto my blue seat, the one with just a few more yellow streaks than the rest, and I jump onto the seat in front of me, making my way to the door just as it opens.

I am thankful for getting off the bus early; I need the scorching cold wind to help settle my soul. I stick my body to the edge of the sidewalk and sink my shoulders inward. I jail my arms close to my torso and take small but quick steps, as though I’ll be noticed if I move too slowly. As though my Arab womanhood would be captured if my existence lingered for too long in a single space. My body has learned to move on, to escape, and to be as unnoticeable as possible – to minimize its presence and to shrink its essence. To morph into the walls, or fill the cracks of a sidewalk. A shiver runs down my spine. I would run but I haven’t run in five years, since the day my grandmother celebrated me starving myself by assuring me that men would be running after me. A week later, my white classmate stole a cigarette from my fingers and stepped on it while asking me why I treat my body like that. Until that day, I hadn’t realized that I treated my body.

I arrive at the bar with a shaken body but a confident soul. Or perhaps it was the opposite. Will I ever know? I walk past infinite booths and pick a table in the dark corner, and sit. I look around the bar. College students drink in herds, women go to the washroom in teams like they’re born with a tacit understanding that no woman should go anywhere alone, and country music demands every ear’s attention. My classmates swarm around me, but my mind is focused on calculations of how long it will take for me to be done with this and be out of this place. One classmate comments on my preoccupation: “It looks like you’re in the midst of an existential crisis.” My body is, I reply.

He asks me to dance.

“I can’t dance to this,” I declare without apology.

“Oh, should we ask for another song?”

I smile and ever so nonchalantly assure him that it’s okay. What else could I say to him? I can’t dance to this because I can’t make my body do things, my friend? I can’t dance to this because my body doesn’t seem to be mine, my friend? Because men around me have claimed ownership over it, even when I don’t know them, even when they are men I meet on a bus on my way to… dance. Dancing tells stories, my friend, but when people keep trying to steal your story, what story do you dance?

“Are you sure you don’t want to dance?”

I wish I was capable, I think, but I say “yes, I’m sure.” Just then, another classmate leans in and warns the audience that maybe I just don’t know how to dance, that maybe they don’t teach girls how to dance in Saudi. The words fill my ears with silence. I bring myself to my feet and stride toward the dance floor. I begin to move my body – or it moves me. We swing our hips in loud jerky movements, it’s almost ugly. Country music fills the air, but my ears do not seem to hear it. My body is responding to the beat of the words replaying themselves in my head, words about castles and paintings, feisty and enticing women that I don’t know.

My eyes closed, I am dancing with my mother. And my sister. And my friends. I am back home with them. The room vibrates with our movements, ceilings shatter and the world softens. Everything disappears but our laughter, loud and obnoxious. Our steps on the ground intense enough to shatter the castle the man in the suit built. We rebuild another one. Hand in hand, we repaint the sky rose. We are not the stars and the stars are not us, they are the words that were rained on us. Our dance is so intense, it shatters the stars.

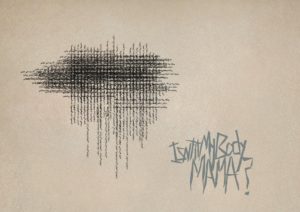

My body cries to mama. What have they done to me, Mama? They take me, they seize me, they mold me into figurines the shape of a pearl, of a treasure, of a flower with booming colors and pure petals, of a chocolate treat waiting to be opened by a deserving man, of a gun blazing in the face of a religion, of an Arab Rapunzel throwing down her hijab from the tower of the oppressed, craving the sight of a white shadow to save her. But all I ever wanted to be was a woman, Mama. So why won’t they let me be, Mama? When will they stop writing my story like a romantic dance, Mama? When will they stop fighting over my body and give it back to me, Mama? Isn’t it my body, Mama?

Just as Mama is about to fill her lungs with a helpless sigh, a vibration stings my pocket and I stop. Mama stops, Majida stops, all the women stop. They know. Of course they know: It’s time to go back home. I reach for my phone and see a missed call from my dad. A text follows: “Wainek?” [where are you?]. Words, words, words.

I go back to my table, like Majida, with nothing but words.